The next big crisis

No, it isn’t revenue related, it isn’t tax related, it’s not another war. It’s the student loan crisis, right around the corner.

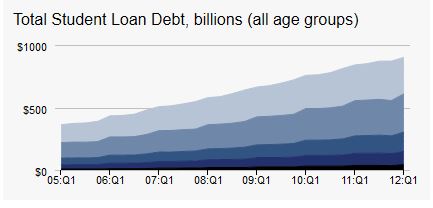

It’s called live now, pay later, or how to go deeply in debt getting your degrees. According to this chart from the New York Federal Reserve it’s a rapidly growing trillion dollar problem; student loans are now second in size to our combined mortgage debt!

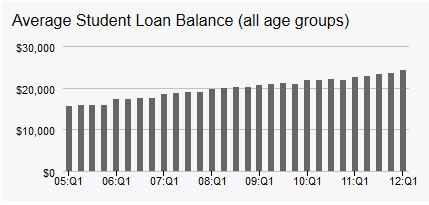

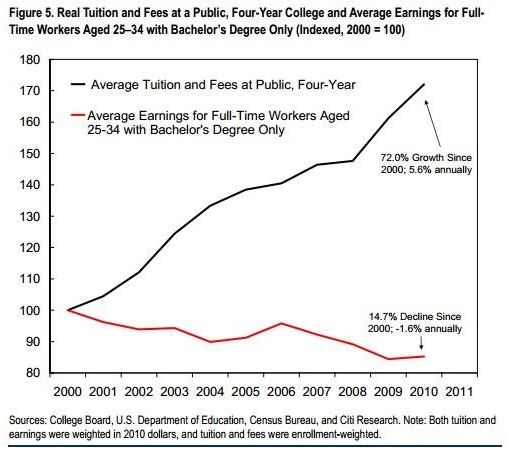

According to the National Center of Education Statistics, if you attended an average four year college in 1980 you typically paid $3,500 a year for total tuition, room and board, in 1990, $6,600, in 2000, $10,800 and 2010, $18,500! When adjusted for inflation, that’s a nearly three times increase in about 30 years. If not adjusted, six times. In other words, if the colleges just increased costs to keep pace with inflation, in 2010, it would have been $9,250. It’s twice as high.

So why have student costs increased sharply, far more than inflation? It’s because it’s easy for students to get loans, insured by our government taxpayers. Why? Because our government is providing incentives for colleges to charge as much as they want, as the mostly (young and unworldly) students have no idea how this particular game is played.

This graph illustrates the problem – Georgia Tech, a part of the University of Georgia system charges an in-state base fee of $40,392 for tuition for a four year degree. An MBA, about $55,000 more. That’s $95,720 of base debt. Even Kennesaw State University, (KSU) my 11th congressional district college currently charges $26,000 for its 120 credit undergraduate program and $55,000 for its MBA program, a total of $81,000. Look up the fees for your local college. They are probably in-line.

Georgia Tech, a part of the University of Georgia system charges an in-state base fee of $40,392 for tuition for a four year degree. An MBA, about $55,000 more. That’s $95,720 of base debt. Even Kennesaw State University, (KSU) my 11th congressional district college currently charges $26,000 for its 120 credit undergraduate program and $55,000 for its MBA program, a total of $81,000. Look up the fees for your local college. They are probably in-line.

The students eventually realize that they are buried in debt, as the colleges are enriched through rapidly growing student contributions to the education business. Yes, a business.

If you have increasing demand for your product, and the government facilitates guaranteed, easy to obtain loans so that your students customers don’t need to pay out-of-pocket costs, and can just defer repayment for years, what’s not to like? It’s a classic live now, pay later scenario.

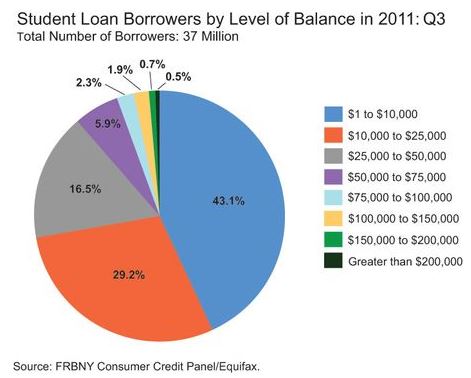

The United States has over 35 million people with student loans, that’s one in four taxpayers. These students are buried in debt, so they have few choices. They can pay the loans off over the years, default immediately or plan a strategic default in the future. Based on observations, many plan for the strategic default, especially as interest rates on these loans are likely to double to over 6%.

Note that most debt is up to $50,000 per student, but a significant number owe between $25-$50,000 and growing fast.

Note that most debt is up to $50,000 per student, but a significant number owe between $25-$50,000 and growing fast.

TransUnion, one of the three largest credit-reporting agencies says that over one-half of these loans are in deferral. When those deferrals end, defaults will increase rapidly.

If homeowners who couldn’t pay their mortgages during the sub-prime crisis were given voluntary payment deferrals as students are, we wouldn’t have had a crisis until much later. They weren’t. They couldn’t pay their mortgages and were foreclosed as fast as the law allowed. When the deferrals expire student loans will soar, as job prospects are weak, salaries are dropping and social media allows discussion of how it’s done.

Defaults are about 10% of non-deferred loans and will increase. As 1/2 of the loans are in deferral status, this means that the default rate is at least 20% of current loans. The students have understood from the housing bubble’s voluntary defaults, that defaults lack social stigma and are even smart. So it’s going to get worse, much worse.

There are three main groups with college loans. The first group spend much of their lives making large monthly payments, (KSU, BA and MBA, $800-900 a month for 10 years, or for the very long term, $350-500 a month for 30 years) shackled by the sheer size of their student debts. Many realize long after the fact that they shouldn’t have signed on for such large debts, but struggle to pay them anyway.

The second group just gives up, and although it’s very difficult to eliminate the debt by bankruptcy, they stop paying and take a hit on their credit rating for a few years. They weigh not paying up to $1,000 a month in debt service, or losing some credit rating points. They choose losing points. There are ways that up to 15% of net pay can be collected by the government, but I suspect that if there is a way to dodge that, it will be.

The third group, plans for the default. They delay making any payments for as long as possible, buy their houses, vehicles, furniture and so on. They get a variety of credit cards, and lines of credit. Everything so they won’t need to apply for credit for the few years while their credit is shot. They then do what the second group does without planning. The same 15% rule applies, but these people plan for the default and structure their lives to avoid repayment.

Our government can also withhold tax refunds, but the former students know enough never to pay too much. Our government can also block federal jobs, but that doesn’t really matter.

In truth, very little can be done. That’s why President Obama made an offer to the students before his reelection that he’d forgive residual student debt after twenty years of payments. Those payments are limited to 10% of disposable income. He was hoping for two things. One, that they’d actually pay steadily for twenty years (good luck with that) until about one-half of the debt was forgiven ($35-$45,000) and two, to buy votes from students at public expense.

Using the $81,000 debt as an example, a student paying 3.4% (subject to Congress doubling it to 6.8%) will pay $360 a month for 20 years, on a 30 year loan. That assumes that he has a greater than $3,600 a month (10% cap) of disposable income. That isn’t likely, so the payments will be less. The student will have paid the bank $42,700 in guaranteed interest plus about $47,000 of his loan back. The public will be stuck with the balance, $34,000. Multiply this by the huge volume of guaranteed loans, and you’re talking real money. Taxpayers money.

I would suggest that it’s better to offer student loans that are capped by type of degree and school, public or private. That capping could be indexed to inflation using a 2000 baseline so the KSU $81,000 tuition loan would be capped at about $64,000. Schools will have to work to keep tuition costs down to the maximum loans available rather than charging what they want. If they go over the loan maximum, students will not enroll.

The only other possibility is that students would no longer claim a degree if they have defaulted on the associated loan, and that the schools would wipe the transcript until the loan is up to date again. But just proposing it is political suicide as former students vote so no one in Congress would dare.

Unfortunately, I suspect that the taxpayers will have to eventually pay the default bills and the students who default will get away with it.