The Love/Hate ratios

There are fourteen Congressional Districts in Georgia, and all were up for grabs in the July 31st Primaries. Each district has about 372,000 voters. Where the seat was contested, the race was won by the incumbent every time, usually by a wide margin. Why was that?

Even when the district had a Republican incumbent, with Democrat challengers, the incumbent got the lion’s shares of the votes cast meaning that the opposing party challengers have little chance of winning in November. Why?

The same goes for a Democrat incumbent, where Republican challengers are trying to unseat the Democrat. Why?

Because of a number of factors. First, incumbents have all the money. Once elected, special interests come out of the woodwork and the committee coffers get rapidly filled.

Not so for the challengers, as they have to work very hard to finance an election effort. If you don’t have more than a few hundred thousand dollars, it’s very difficult to win as voters don’t know who you are. You haven’t mailed them, you haven’t had media campaigns and the newspapers show little interest as you’re not the front runner.

Second, it’s called Gerrymandering, the process of designing districts so one side or the other can easily win, as the districts by the party in power when the redistricting occurs. The geographic boundaries drawn to favor one side or the other depending on who is running the state at that time.

This means that, barring some unusual and unexpected events, the voters are happy with the incumbents and it will be business as usual.

I noticed that in my district, Phil Gingrey the Republican incumbent didn’t appear to spend much money on his campaign so he thinks that he’s safe. According to the numbers, he is.

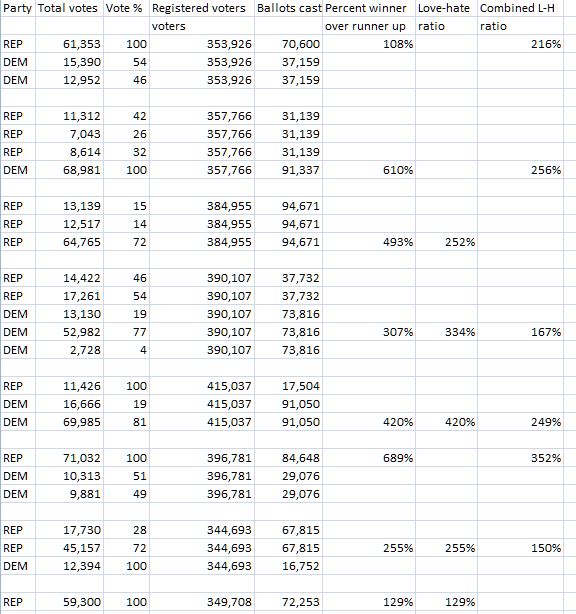

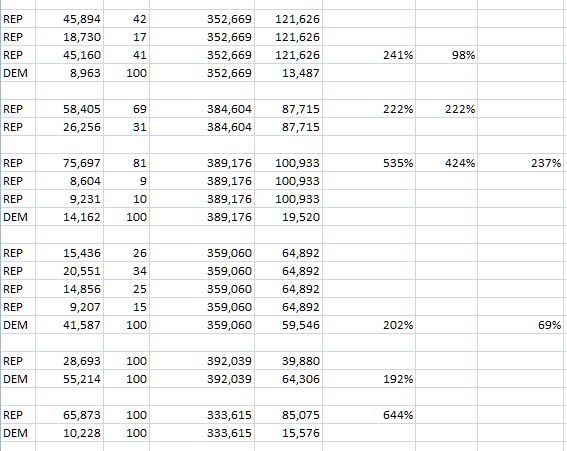

Below you’ll see my Love-Hate ratios. If you look at the last two columns, the first of the two shows the ratio of the winner’s vote tally compared to the combined tally of the other party’s votes. To illustrate, Lynn Westmoreland got over 250% of the combined votes of his Republican challengers so is very likely to be elected again and again and again, unless he makes a big mistake and the voters notice.

The last Love-Hate ratio column illustrates that if the same party voters join forces with the opposing party, and vote for the other party’s candidate that it is an indicator of who will win in that race.

For example, John Barrow in the 12th District is the most likely to lose, even though an incumbent. The rest should easily win, unless they also make some big mistakes and the voters notice.

Fortunately for them, voters pay little attention to politics unless to grumble, until the election date, so any transgressions are of little significance to the candidate’s chances.